This archive of images traces trauma on two levels — the individual, by writing the trauma of the person killed onto the physical location of their killing; and the communal, by creating a collective memory of the transgender family we have lost to senseless violence. The project offers an opportunity to mourn for the person and mourn for our society and our lack of accountability for this ongoing genocide. Our lack of protection for black life is on the backs of every non-black person and is our responsibility as white people to dismantle white supremacy and kill this disease we are benefiting from.

This work is a heartbreaking anthropological document, as a discreet record of loss for the transgender community. This project utilizes google maps by creating a subversion of a surveillance technology that is most often used to police similar marginalized communities and intended to erase them (through police violence, the prison industrial complex, lack of access to medical care, and poverty). These satellite images create a placement for the viewer and an immediate connection to the trans bodies that took their last breath in these locations. The deaths of trans people is a genocide, a mass slaughter- specifically trans women of color. This project aims to bring awareness to this reality through subtle images of space.

2020

2019

2018

2017

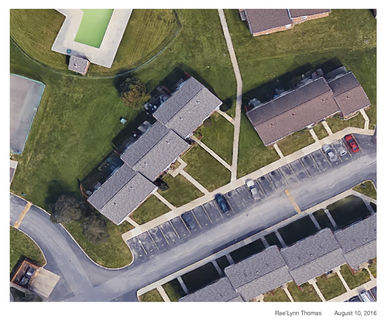

2016

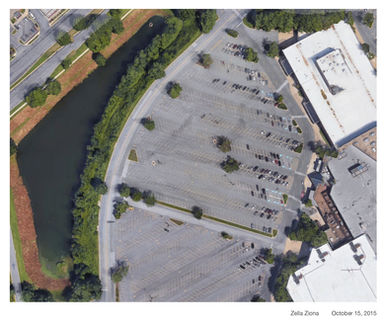

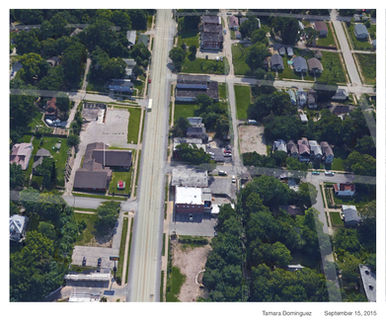

2015

I began working on Mapping a Genocide in 2015. That fall, I attended an event in West Hollywood for Transgender Day of Remembrance, held annually on November 20th to memorialize folks who have been murdered as a result of transphobia and remind our cisgender allies of the continued violence endured by the transgender community. At the memorial, transgender activists and our cisgender accomplices read the names of those transgender people who were killed that year. I was struck not only with how many names there were to read, but also with how many geographical locations were represented. I began scouring crime and news reports to see where these murders were taking place. The answer was… everywhere.

I had expected my research to reveal some theme of space, whether that be rural or urban, alleys or deserted places, to show that there was perhaps a kind of place that posed more danger to a transgender body than others. But these murders happen everywhere — in homes, on doorsteps, in parks, in alleys, river beds, next to police stations, and the list continues. When I looked up these addresses on Google Maps, I was struck with their banality; they were just another street corner, just another backyard, just another piece of pavement. There were no markers to indicate here was a site of great tragedy, and I wanted to create those markers. I began by screen capturing the Google Map satellite depictions of these locations. I then edited all of the text out of the images, and added the name of the person killed and the date of their murder to every image. I thus created an archive spanning 2015-present, documenting every reported transgender murder in the United States. This archive traces trauma on two levels — the individual, by writing the trauma of the person killed onto the physical location of their killing; and the communal, by creating a collective memory of the transgender family we have lost to senseless violence. The project offers an opportunity to mourn for the person and mourn for our society and our lack of accountability for this ongoing genocide.

...abject is fundamental to the maintenance of subjectivity and society, while the condition to be abject is subversive of both formations. Is the abject, then, disruptive of subjective and social orders or foundational of them, a crisis in these orders or a confirmation of them? If subjectivity and society abject the alien within, is abjection not a regulatory operation? ( Foster, Hal. “Obscene, Abject, Traumatic.” October, vol. 78, 1996, pp. 107–124. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/778908.)

But this is a difficult project. The images operate as mirror abjection — the process by which we separate ourselves from that which threatens our self-identity. Julia Kristeva developed the idea of abjection as a way we separate from an object in order to protect ourselves from dealing with tragedy. In the case of Mapping a Genocide, the object itself (the images) help us with the abjection because they are not a literal representation of the trauma itself, but rather of the places where the trauma happened without leaving a permanent trace. They remind us without directly confronting us, or perhaps confront us without reminding us (of the horror of trauma).

To further complicate things, there is the question of memorialization as arts practice — why are these images works of art, when the contemporary art world already capitalizes upon identity and trauma and erases intention so often? Is the intended confrontation erased when it intersects with art markets and capitalism? Are these images art or are they tragedy? Historically, we have analyzed photography, specifically photojournalism, with this very question in mind. And still photojournalism doesn’t exist within the confines of the same art world I am referring to, the contemporary and often-appropriative market-based art world that desperately exploits work that examines race, class and gender and is rooted in an unfettered capitalism, oftentimes the antithesis of the work and artists it seeks to market."

From “Tracing Trauma.” On The Bus, BazBam Press, 2018, pp. 100–105. and Ed. Quinn, Therese, and Lauren De Jesus. Fwd: Museums: Home. StepSister Press, 2020. By Museums and Exhibition Studies Program at University of Illinois at Chicago.